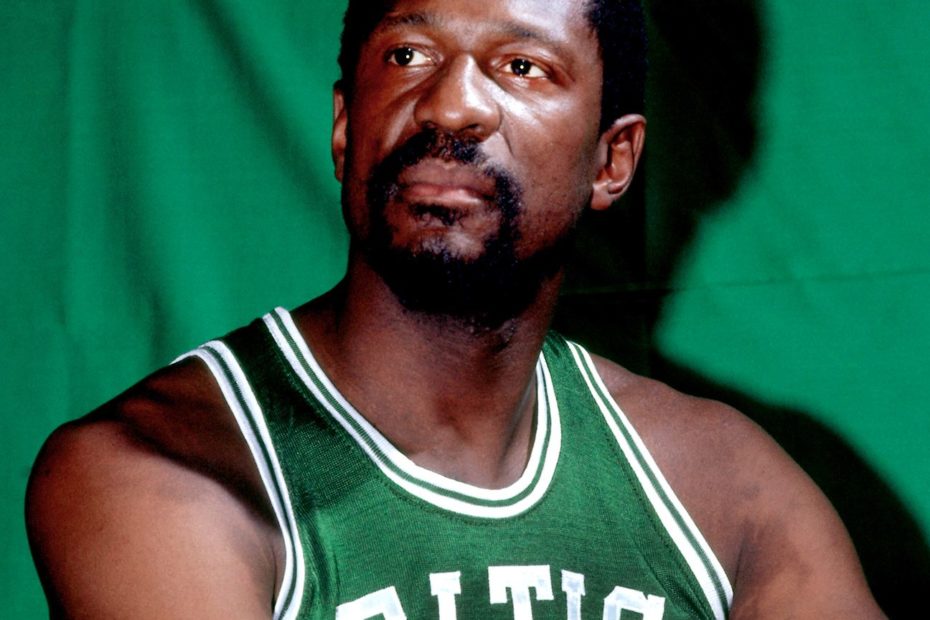

Bill Russell, the cornerstone of the Boston Celtics dynasty that won eight straight titles and 11 overall during his career, died Sunday. The Hall of Famer was 88.

Russell died “peacefully” with his wife, Jeannine, at his side, a statement posted on social media read. Arrangements for his memorial service will be announced soon, according to the statement.

The statement did not give the cause of death, but Russell, who had been living in the Seattle area, was not well enough to present the NBA Finals MVP trophy in June because of a long illness.

“But for all the winning, Bill’s understanding of the struggle is what illuminated his life,” the statement said. “From boycotting a 1961 exhibition game to unmask too-long-tolerated discrimination, to leading Mississippi’s first integrated basketball camp in the combustible wake of Medgar [Evers’] assassination, to decades of activism ultimately recognized by his receipt of the Presidential Medal of Freedom … Bill called out injustice with an unforgiving candor that he intended would disrupt the status quo, and with a powerful example that, though never his humble intention, will forever inspire teamwork, selflessness and thoughtful change.

An announcement… pic.twitter.com/KMJ7pG4R5Z

— TheBillRussell (@RealBillRussell) July 31, 2022

“Bill’s wife, Jeannine, and his many friends and family thank you for keeping Bill in your prayers. Perhaps you’ll relive one or two of the golden moments he gave us, or recall his trademark laugh as he delighted in explaining the real story behind how those moments unfolded. And we hope each of us can find a new way to act or speak up with Bill’s uncompromising, dignified and always constructive commitment to principle. That would be one last, and lasting, win for our beloved #6.”

Over a 15-year period, beginning with his junior year at the University of San Francisco, Russell had the most remarkable career of any player in the history of team sports. At USF, he was a two-time All-American, won two straight NCAA championships and led the team to 55 consecutive wins. And he won a gold medal at the 1956 Olympics.

During his 13 years in Boston, he carried the Celtics to the NBA Finals 12 times, winning the championship 11 times, the last two titles won while as both a player and serving as the NBA’s first Black coach.

“Bill Russell’s DNA is woven through every element of the Celtics organization, from the relentless pursuit of excellence, to the celebration of team rewards over individual glory, to a commitment to social justice and civil rights off the court,” the Celtics said in a statement. “Our thoughts are with his family as we mourn his passing and celebrate his enormous legacy in basketball, Boston, and beyond.”

NBA commissioner Adam Silver called Russell “the greatest champion in all of team sports” in a statement Sunday.

“I cherished my friendship with Bill and was thrilled when he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom,” Silver said. “I often called him basketball’s Babe Ruth for how he transcended time. Bill was the ultimate winner and consummate teammate, and his influence on the NBA will be felt forever.”

A five-time MVP and 12-time All-Star, Russell was an uncanny shot-blocker who revolutionized NBA defensive concepts. He finished with 21,620 career rebounds — an average of 22.5 per game — and led the league in rebounding four times. He had 51 rebounds in one game, 49 in two others and posted 12 straight seasons with 1,000 or more rebounds. Russell also averaged 15.1 points and 4.3 assists per game over his career.

Until Michael Jordan’s exploits in the 1990s, Russell was considered by many as the greatest player in NBA history.

“Bill Russell was a pioneer — as a player, as a champion, as the NBA’s first Black head coach and as an activist,” Jordan, now the chairman of the Charlotte Hornets, said in a statement. “He paved the way and set an example for every Black player who came into the league after him, including me. The world has lost a legend. My condolences to his family and may he rest in peace.”

Russell was awarded the Medal of Freedom by former President Barack Obama in 2011, the nation’s highest civilian honor. And in 2017, the NBA awarded him with its Lifetime Achievement Award.

“Today, we lost a giant,” Obama said in a statement Sunday. “As tall as Bill Russell stood, his legacy rises far higher — both as a player and as a person. Perhaps more than anyone else, Bill knew what it took to win and what it took to lead.”

President Joe Biden, in a statement released by the White House, praised Russell for his lifelong work in civil rights as well as in sports, and called him “a towering champion for freedom, equality, and justice.”

“Bill Russell is one of the greatest athletes in our history — an all-time champion of champions, and a good man and great American who did everything he could to deliver the promise of America for all Americans,” Biden said.

William Felton Russell was born Feb. 12, 1934, in Monroe, Louisiana. His family moved to the Bay Area, where he attended McClymonds High School in Oakland. He was an awkward, unremarkable center on McClymonds’ basketball team, but his size earned him a scholarship at San Francisco, where he blossomed.

“I was an innovator,” Russell told The New York Times in 2011. “I started blocking shots although I had never seen shots blocked before that. The first time I did that in a game, my coach called timeout and said, ‘No good defensive player ever leaves his feet.'”

Russell did it anyway, and he teamed with guard K.C. Jones to lead the Dons to 55 straight wins and national titles in 1955 and 1956. (Jones missed four games of the 1956 tournament because his eligibility had expired.) Russell was named the NCAA tournament Most Outstanding Player in 1955. He then led the U.S. basketball team to victory in the 1956 Olympics at Melbourne, Australia.

With the 1956 NBA draft approaching, Celtics coach and general manager Red Auerbach was eager to add Russell to his lineup. Auerbach had built a high-scoring offensive machine around guards Bob Cousy and Bill Sharman and undersized center Ed Macauley but thought the Celtics lacked the defense and rebounding needed to transform them into a championship-caliber club. Russell, Auerbach felt, was the missing piece to the puzzle.

After the St. Louis Hawks selected Russell in the draft, Auerbach engineered a trade to land Russell for Macauley.

Boston’s starting five of Russell, Tommy Heinsohn, Cousy, Sharman and Jim Loscutoff was a high-octane unit. The Celtics posted the best regular-season record in the NBA in 1956-57 and waltzed through the playoffs for their first NBA title, beating the Hawks.

In a rematch in the 1958 Finals, the Celtics and Hawks split the first two games at Boston Garden. But Russell suffered an ankle injury in Game 3 and was ineffective the remainder of the series. The Hawks eventually won the series in six games.

Russell and the Celtics had a stranglehold on the NBA Finals after that, going on to win 10 titles in 11 years and giving professional basketball a level of prestige it had not enjoyed before.

In the process, Russell revolutionized the game. He was a 6-foot-9 center whose lightning reflexes brought shot-blocking and other defensive maneuvers that trigger a fast-break offense into full development.

In 1966, after eight straight titles, Auerbach retired as coach and named Russell as his successor. It was hailed as a sociological advance, since Russell was the first Black coach of a major league team in any sport, let alone so distinguished a team. But neither Russell nor Auerbach saw the move that way. They felt it was simply the best way to keep winning, and as a player-coach, Russell won two more titles over the next three years.

Their biggest opponent was age. After he won his 11th championship in 1969 at age 35, Russell retired, triggering a mini-rebuild. During his 13 seasons, the NBA had expanded from eight teams to 14. Russell’s Celtics teams never had to survive more than three playoff rounds to win a title.

“If Bill Russell came back today with the same equipment and the same brainpower, the same person exactly as he was when he landed in the NBA in 1956, he’d be the best rebounder in the league,” Bob Ryan, a former Celtics beat writer for The Boston Globe, told the San Francisco Chronicle in 2019. “As an athlete, he was so far ahead of his time. He’d win three, four or five championships, but not 11 in 13 years, obviously.”

In 2009, the MVP trophy of the NBA Finals was named in Russell’s honor — even though he never won himself, because it wasn’t awarded for the first time until 1969. Russell, however, traditionally presented the trophy for many years, the last time in 2019 to Kawhi Leonard; Russell was not there in 2020 because of the NBA bubble nor in 2021 due to COVID-19 concerns.

Along with multiple titles, Russell’s career also was partly defined with his rivalry against Wilt Chamberlain.

In the 1959-60 season, the 7-foot-1 Chamberlain, who averaged a record 37.6 points per game in his rookie year, made his debut with the Philadelphia Warriors. On Nov. 7, 1959, Russell’s Celtics hosted Chamberlain’s Warriors, and pundits called the matchup between the best offensive and defensive centers “The Big Collision” and “Battle of the Titans.” While Chamberlain outscored Russell 30-22, the Celtics won 115-106, and the game was called a “new beginning of basketball.”

The matchup between Russell and Chamberlain became one of basketball’s greatest rivalries. One of the Celtics’ titles came against Chamberlain’s San Francisco’s Warriors teams in 1964.

Although Chamberlain outrebounded and outscored Russell over the course of their 142 career head-to-head games (28.7 rebounds per game to 23.7, 28.7 points per game to 14.5) and their entire careers (22.9 RPG to 22.5, 30.1 PPG to 15.1), Russell usually got the nod as the better overall player, mainly because his teams won 87 (61%) of those games.

In the eight playoff series between the two players, Russell and the Celtics won seven. Russell has 11 championship rings; Chamberlain has just two.

“I was the villain because I was so much bigger and stronger than anyone else out there,” Chamberlain told the Boston Herald in 1995. “People tend not to root for Goliath, and Bill back then was a jovial guy and he really had a great laugh. Plus, he played on the greatest team ever.

“My team was losing and his was winning, so it would be natural that I would be jealous. Not true. I’m more than happy with the way things turned out. He was overall by far the best, and that only helped bring out the best in me.”

After Russell retired from basketball, his place in its history secure, he moved into broader spheres, hosting radio and television talk shows and writing newspaper columns on general topics.

In 1973, Russell took over the Seattle SuperSonics, then a 6-year-old expansion franchise that had never made the playoffs, as coach and general manager. The year before, the Sonics had won 26 games and sold 350 season tickets. Under Russell, they won 36, 43, 43 and 40 games, making the playoffs twice. When he resigned, they had a solid base of 5,000 season tickets and a team that reached the NBA Finals the next two years.

Russell reportedly became frustrated over the players’ reluctance to embrace his team concept. Some suggested that the problem was Russell himself; he was said to be aloof, moody and unable to accept anything but the Celtics tradition. Ironically, Lenny Wilkens guided Seattle to a championship two years later, preaching the same team concept that Russell had tried to instill unsuccessfully.

A decade after he left Seattle, Russell gave coaching another try, replacing Jerry Reynolds as coach of the Sacramento Kings early in the 1987-88 season. The team staggered to a 17-41 record, and Russell departed midseason.

Between coaching stints, Russell was most visible as a color commentator on televised basketball games. For a time he was paired with the equally blunt Rick Barry, and the duo provided brutally frank commentary on the game. Russell was never comfortable in that setting, though, explaining to the Sacramento Bee, “The most successful television is done in eight-second thoughts, and the things I know about basketball, motivation and people go deeper than that.”

He also dabbled with acting, performing in a Seattle Children’s Theatre show and an episode of “Miami Vice,” and he wrote a provocative autobiography, “Second Wind.”

Russell became the first Black player to be inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 1975, and in 1980 he was voted Greatest Player in the History of the NBA by the Professional Basketball Writers Association of America. He was part of the 75th Anniversary Team announced by the NBA in October 2021.

In 2013, Boston honored Russell with a statue at City Hall Plaza.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.