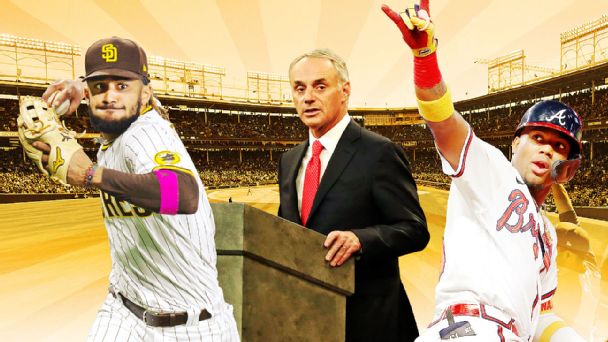

Editor’s note: From rising strikeout totals and unwritten-rules debates to connecting with a new generation of fans and a looming labor battle, baseball is at a crossroads. As MLB faces these challenges, we are embarking on a season-long look at The State of Baseball, examining the issues and storylines that will determine how the game looks in 2021 and far beyond.

Congratulations, you’ve been named acting commissioner of Major League Baseball for a single day.

Assuming you were given unlimited power during your brief tenure, what’s the first thing about the league that you would change? And how would it make the game better, whether it’s on or off the field? The only rule: It has to be realistic. No expansion teams on the moon — just changes that could be implemented today.

That’s what we presented to ESPN MLB experts Bradford Doolittle, Alden Gonzalez, Tim Keown, Joon Lee, Kiley McDaniel, Jeff Passan, Jesse Rogers and David Schoenfield — and we got a range of ideas, from the subtle to the radical.

Here are their eight proposals.

Shorten the season

The MLB regular season should be shortened by a month.

Baseball hums along just fine as America’s summer sport. The July 31 trade deadline provides energy and momentum at a time when it’s needed, but not long after teams welcome their new players, the dog days of August are upon us.

By the time the pennant races begin to heat up in September, the country has mostly moved on to football and even the start of other sports’ seasons. October arrives more with a whimper these days.

And that’s not even mentioning the teams out of the race: One month of meaningless baseball to rate prospects is just fine. Two months is too long. It always has been.

Picture this: The excitement of the trade deadline leads right into the pennant races. As football inches its way to the starting gate, baseball ends its season with a bang. September playoffs won’t feel secondary to the pigskin sport; they’ll be right next to it in the headlines.

The secondary impacts of a shorter season only bring positives. Careers of star players, especially pitchers, could last longer, making up for the loss of revenue for them because of fewer games. Within a season, there would be less reason for star players to take games off. Stands would be filled even more with fewer games to choose from. Playoff weather would no longer be an issue.

As for the crusty, old-school fan who cherishes baseball’s numbers over 162 games, those days are long gone. Counting stats are out and percentages are in. An OPS based on 132 games will still have the same meaning as it did based on 162. — Jesse Rogers

Expand and realign the leagues by geography

I’d like to see baseball expand to 32 teams sooner rather than later. When that happens, baseball will have an opportunity to leverage the regional appeal of the sport with a revised structure. As a traditionalist, this would offend my history-loving sensibilities. But since it’s probably inevitable anyway, once MLB grows it’ll be time to rip off the Band-Aid and go heavy on geography-based realignment.

That means the timeworn American and National League designations go away. If you start shifting teams that have been around for 120 years, I don’t see how you keep the league labels as they are. You’d go to an Eastern League and a Western League, each with two eight-team divisions, and within each division, you’d have two four-team pods. The playoffs would include six teams per league, with the four division champions earning a first-round bye.

The geographic pods within each division are important for scheduling reasons: These will be the most frequent matchups on the schedule. The winner of each “pod” will get a playoff spot, unless that team is the overall division winner, in which case the next-best team in the pod gets to go.

Finally, I’d arrange broadcast distribution like this: You’d have different levels of subscription access, and blackout rules will no longer apply. You can get an MLB-level subscription, a division subscription, a pod subscription or a subscription for an individual team. These would be stand-alone subscriptions for non-national broadcasts, so that Fox, ESPN, etc., would still broadcast games to which all fans would have access. These would be showcase games.

The driving force behind all this is regionalization. Build those rivalries, starting in the minors, which have already become more geographically aligned and presumably will only become more so over time. You don’t ignore the national aspect, but baseball is already local to a significant degree. The structure of the sport ought to reflect that. — Bradford Doolittle

Add a pitch clock

Hall of Fame owner Bill Veeck, in his autobiography published in 1962, wrote, “The game has become too slow. There would be nothing wrong with the now standard three-hour game if we were presenting two and a half hours of action.”

If that sounds familiar, Theo Epstein said this earlier this year: “We need to find a way to get more action into the game, get the ball in play more often, allow players to show their athleticism some more, and give fans more of what they want.”

Baseball, of course, used to have a clock that forced a faster-played game: the sun. Barring a return to day games and tearing down stadium lights, we need a different solution to create fewer strikeouts, more action and a more rapid pace.

The solution: a pitch clock. It’s used in the minor leagues. The Olympics deployed one without runners on base. It works. We need it in the majors.

1. Time between pitches is the biggest reason games are longer than ever — 23 minutes longer than 2005 for a nine-inning game, 34 minutes longer than 1984 (and 35 minutes longer than 1962). A few years ago, Grant Bisbee studied two nearly identical games in terms of score, pitches thrown and baserunners — one from 1984 and one from 2014 — and found nearly 33 additional minutes elapsed in the 2014 game in dead time between pitches.

2. Rob Arthur’s study at FiveThirtyEight in 2017 showed that velocity increases when pitchers take more time between pitches. With pitchers maxing out more than ever on every pitch — especially relievers, who are throwing a higher percentage of innings than in 1962 or 1984 — that walk around the mound and wipe of the brow adds up over 290 pitches.

So institute a pitch clock and force batters to remain in the box. Both sides lose a little something, but pitchers will be forced to work faster and they probably won’t throw quite as hard. Command pitchers who work fast (think Mark Buehrle) will be more in demand, batters will make more contact and fielders will get more opportunities to display their athleticism. — David Schoenfield

Bring in the robo umps

The concept of the strike zone is simple. The stewards of the game identify a vertical space over the irregular pentagon that is home plate. If a pitcher throws a baseball in that space over the plate, it is a strike. Anything else is a ball. This sounds easy.

It is not. It is not easy because the human eye is fallible and the human brain susceptible to bias. It is not easy because catchers have been taught to exploit these fallibilities and biases. It is not easy because umpires who get 95% of ball-strike calls correct are considered the best of the best, and umpires who get 85% right remain employed, and every single day there are manifold examples of balls that are called strikes and strikes that are called balls.

It is time to end this charade and transition to the era of the robot umpire. MLB has christened this system ABS — automated balls and strikes — because robot umpires sound like something Boston Dynamics would make. I don’t care if it’s a creepy Chuck E. Cheese animatronic behind home plate. If it calls balls and strikes accurately and consistently, it will be a massive upgrade.

Yes, the technology remains a work in progress. Breaking balls are a challenge. So is defining a hitter’s proper strike zone. And the league-wide zone may adapt over time, as it often does. But at least it won’t by dozens of different interpretations of the zone by individual umps. The underpinnings of the system are sound. The iterations being made after use in the Low-A Southeast League are instructive.

I, for one, welcome our new robot overlords. — Jeff Passan

End streaming blackouts and loosen video rights restrictions

Last week’s Field of Dreams experiment was an opportunity for Major League Baseball to break the mid-August monotony of the baseball season — a marquee event with a pop culture tie-in to an iconic movie, and a made-for-TV spectacle in the cornfields of Iowa.

Yet if you tried to watch a baseball game in Iowa through the MLB.tv streaming service, you’d be met with blackouts not only for that night’s national broadcast, but for any White Sox, Cubs, Twins, Brewers, Cardinals or Royals game. Dyersville, Iowa, is located four hours from Chicago, four hours from Minneapolis, three hours from Milwaukee and more than five hours from St. Louis and Kansas City. If you live in New York, you could access games in Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington, D.C., all roughly equivalent to, or shorter than, the distances of those cities from Dyersville.

Today’s young cord-cutters primarily rely on streaming services, social media and YouTube. By blacking out games on MLB.tv — the easiest way to watch across the country — the league continues to stunt its potential growth among those fans, plus any fans blacked out because of geography. The league needs to work with its TV providers to make streaming local games much easier.

It’s not just blackouts: While MLB has loosened its social media video policies in recent years, the league would be prudent to further embrace the rise of social media as the dominant conversation-and-consumption platform for fans. The future is on social media, in the hands of fans, and MLB needs to make creating baseball-themed videos using game content as seamless as possible by loosening its reins on copyright violations — similar to the NBA, which treats user-generated content like free advertising for the sport. — Joon Lee

Allow the trading of draft picks

I think a rule change that seems subtle now but could have the biggest impact on the sport is allowing the trading of draft picks. It’s not guaranteed to come in the next CBA, but I’d say it’s more likely than not at this point.

Right now, any simple one-for-one MLB trade requires both teams to have comparable evaluations on both players. With picks on the table, all 30 teams will value the pick essentially the same, and you just need to match up on the valuation of one player. Every team, regardless of where it is in the competitive cycle, will want picks in a deal due to the universal value. Just doing this will make a trade twice as likely to happen as it is right now.

There’s also another obvious positive of creating movement in the draft: It’s good for the popularity of the event. Big leaguers could now be a part of the proceedings with trades and more rumors for fans to follow. Doing this would also likely mean hard-slotted picks with a static bonus rather than just a pool amount, making every player available for every team and leading to a format that’s easier for casual fans to understand.

The draft becoming more dynamic creates more interest and revenue around that event and other associated events (the College World Series and maybe a new international draft TV event?). This would also give innovative teams more ways to be on the cutting edge (always a positive) and scouts more ways to create value for their clubs. It might even create more jobs for scouts since more players could be picked by each team, making more scouting reports necessary for each club. — Kiley McDaniel

Pay minor leaguers a living wage

Minor league life has been portrayed with a certain charm over the years. The long bus rides, the endless string of peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, the tiny apartments — all of it depicted as a necessary rite of passage, even though the reality is a lot colder and darker.

It’s exploitation.

Minor league salaries actually rose between 38% and 72% in 2021, with players from rookie level to Triple-A making somewhere between $400 to $700 a week during the season. It’s an improvement, but it isn’t enough. And there are still countless anecdotes of minor leaguers sleeping in cars and apartments infested with cockroaches and players practically starving themselves because their paychecks aren’t large enough to cover their living expenses.

An antitrust exemption allows major league owners to suppress the wages of minor league players, a freedom they have long abused. Major League Baseball’s recent contraction of the minor leagues was sold as a structural change that would improve the quality of life for minor league players, but that has not been the case. In fact, as detailed in a recent piece by The Athletic, the housing crisis triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic has only worsened conditions.

Minor league players don’t have representation by the MLB Players Association. And their peers at the major league level, for the most part, don’t fight for them in collective bargaining, largely because they all went through something similar. That doesn’t make it OK. Improving the quality of life for minor leaguers will improve the quality of their play, which will improve the quality of baseball in cities throughout the country, which will elevate the sport.

But this is about something significantly more important than that — this is about treating people with common decency. — Alden Gonzalez

Rethink the role of the commissioner

The first order of business for me, the new Grand Potentate of Baseball, is to address the tenuous nature of baseball’s time-honored ability to overcome the incompetence, greed and short-sightedness of the those who run it.

The problem starts right at the top: The commissioner represents the game, but in the end, he works for the owners. Rob Manfred, for instance, has been undeniably good for the bank accounts of the men who own teams — and bad for just about everyone else. Under his watch, the sport has faced a list of public-relations disasters that wouldn’t fit on a lineup card.

The game will survive. It always does. But while the commissioner instead is focusing on the DH and extra innings and seven-inning doubleheaders, the sport is getting smaller, more regional, less inclusive. Youth baseball needs to be revamped before every poor kid is completely redlined out of the game. Owners need to be held accountable for willfully failing to field competitive teams. Women need to have more powerful roles in redefining the culture. Conditions in the minor leagues, where players are bunking five to a room and struggling to afford food, need to be addressed before they ignite a full-on mental-health crisis.

The best path to improving the state of baseball? It starts by installing a commissioner whose relationship to the game goes deeper than financial concerns, someone who stands for something other than sponsorships and real-estate deals for billionaire owners. Someone who understands there are constituents — in the game’s operations departments, in the clubhouses, in the stands — who actually like the game for what it is, and not for how much can be extracted from it. — Tim Keown