One of my favorite movies is “Midnight in Paris.” Owen Wilson plays Gil, a writer who transports back in time every night to what he considers the golden era — 1920s Paris, where he encounters the Lost Generation and hangs out with Hemingway, Fitzgerald and Picasso, among others. He meets a woman named Adriana, and one evening they end up in Belle Époque Paris, Adriana’s favorite golden age. They meet the painters Edgar Degas, Paul Gauguin and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, who suggest the Renaissance was the greatest era.

It’s a film about our love for nostalgia — something almost any Major League Baseball fan can relate to — and our yearning for times other than our own. Gil implores Adriana to come back with him to 1920s Paris. “Adriana, if you stay here, though, and this becomes your present, then pretty soon you’ll start imagining another time was really your … you know, was really the golden time,” Gil says. “Yeah, that’s what the present is. It’s a little unsatisfying because life’s a little unsatisfying.”

So I apologize in advance if this piece comes across as a little nostalgic for the 1980s. That was my golden era. Was baseball really better in the ’80s? No. I mean, Astroturf sucked, although it did help fuel a style of play that added excitement to the game. Today’s ballparks are vastly superior, with better sightlines, more comfortable seats and a cornucopia of tastier food and beverage options. We now have access to every game and every highlight — in real time, on our phones. And, yes, today’s athletes are stronger, are better conditioned, throw harder and are privy to all the data that can help them improve.

On the other hand, there are things players did in the 1980s that nobody does today. It was a game with a wide diversity of play: speed and power, power pitchers and finesse artists, contact magicians and swing-for-the-fences sluggers. I’ve selected eight seasons that help define the decade — not the eight best, but eight remarkable seasons that couldn’t exist in 2020. Eight seasons that make the 1980s a golden era.

Rickey Henderson, 1982 A’s (130 stolen bases)

Pause for a moment — something Henderson rarely did in 1982. Think about what it takes to steal 130 bases in one season, to beat up your body with all the attempts, all the pickoff throws, all the headfirst airplane landings at second base and third base. “His desire to run is constant,” teammate Davey Lopes said that season. “The country just doesn’t realize what an accomplishment this is. It’s comparable to Joe DiMaggio’s hit streak. And he’s doing it with a slide that has more disadvantages than advantages. He can hurt his chest, shoulders and hands. The ball can hit him on the head. An infielder can land with his spikes on his hands.”

Henderson was 23 years old in 1982. He had stolen 100 bases in 1980 and 58 in the strike-shortened season of 1981. Lou Brock’s record of 118 was just eight years old at the time. Under manager Billy Martin, Henderson’s pursuit of Brock was relentless. According to Baseball-Reference.com, Henderson had 225 stolen-base opportunities when he was on first or second base without a runner on directly in front of him. He had 172 stolen-base attempts — which means he also was caught stealing 42 times (also a record). Even if we eliminate the 16 times he was picked off, that means he attempted a steal about 70% of his possible opportunities. He attempted 47 steals of third base alone. The audacity of youth.

In one August game, the Red Sox pitched out three times in one plate appearance with Henderson at first base — even though the A’s were leading 11-5. That upset Martin. Henderson did not have a green light, and Martin wasn’t about to send him with a six-run lead. After the three pitchouts, however, Henderson stole on the 3-0 count. The Red Sox railed against Henderson for breaking baseball etiquette. Martin blamed the Red Sox for provoking the situation.

Henderson wasn’t the only player running wild in the 1980s, with stolen-base attempts peaking in MLB in 1987, with an average of 1.21 per game (per team). That figure in 2019 was 0.64 per game, barely half of the 1987 total and the lowest since 1964. Mallex Smith led the majors in steals with 46. The top three players combined fall one steal short of Henderson’s total. Why run and risk an out when the next batter might hit a home run?

It makes the game less interesting, however, and nobody created that sense of anticipation like Henderson. Every steal attempt was its own little drama. “You know, every day now for the past two weeks when I’ve seen Rickey take off, I’ve felt chills run through me,” teammate Dwayne Murphy said as Henderson closed in on Brock’s record. “It’s been that exciting.”

Dwight Gooden, 1984 Mets (19 years old, 218 IP, 276 K’s, 2.60 ERA)

No, I don’t think we’ll be seeing a teenager throw 218 innings in the majors anytime soon. The only 19-year-old in the majors in 2019 was Blue Jays reliever Elvis Luciano, a Rule 5 pick who threw 33⅔ innings. The most innings from a 19-year-old in the minors was 132⅓ from Yankees farmhand Roansy Contreras, pitching in Low A. Luis Patino was the top 19-year-old pitching prospect in 2019, and the Padres limited him to 94⅔ innings.

While 1985 was Gooden’s iconic Cy Young season for the ages, his rookie season was more stunning. How could a teenager be this good? His 11.4 strikeouts per nine innings set a record for starting pitchers (it now ranks 30th), but at the time was better than Ryan or Koufax or Feller or anybody else. Nobody had even reached 11.0 per nine. In September, he pitched consecutive games with 16 strikeouts (and fired a one-hit shutout in the start before those two). He remains the only the pitcher with at least 16 strikeouts in back-to-back starts.

Of course, it was harder to follow the ride back then. Unless you lived in New York, you had to wait until the next day’s paper to check the reports and box scores. You hoped he would start on the national TV Game of the Week. If you were lucky, you were an early subscriber to cable and watched a fledgling network called ESPN. My family got cable late that season, and I would tape SportsCenter just to watch the Gooden highlights.

In 1985, Gooden threw 276⅔ innings. Nobody has topped that since 1987. Only one 20-year-old since then has pitched even 200 innings in a season. Gooden was never again as great as those first two seasons, for complicated reasons, but perhaps in part because of all that work at a young age. Are teams too cautious with young pitchers now? Probably. Is it the right thing to do? Probably. But what were the Mets supposed to do? Gooden was too good to hold back.

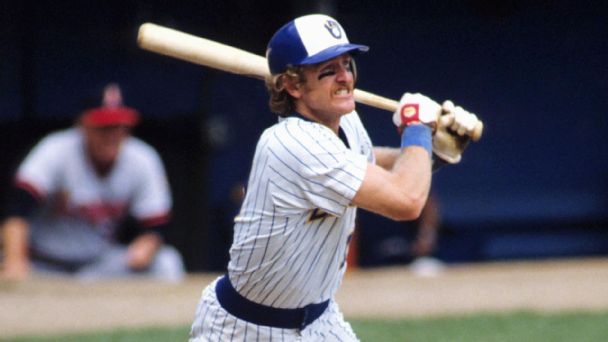

Ryne Sandberg, 1984 Cubs (.314, 36 doubles, 19 triples, 19 home runs, 32 SB)

You want to talk about a season in which a player did a little bit of everything? Sandberg hit doubles, he hit triples, he hit home runs, he stole bases, he won a Gold Glove, he played 156 games — and the Cubs made the postseason for the first time since 1945. He led the league in runs and triples and bashed 200 hits to win MVP honors.

What I love is the “everything” part of Sandberg’s season. Obviously, triples are scarce today for a couple of reasons: more home runs and smaller parks. But you also need speed, and you need to be busting it out of the batter’s box. The major league lead for triples in 2019 was just 10 (and three of the four players who hit 10 were Royals). The last player to hit 15 was Eddie Rosario in 2015. The last player to hit at least 30 doubles, 15 triples, 15 home runs and steal 30 bases was Jose Reyes in 2008. Juan Samuel actually filled all those buckets in 1984 as well.

Here’s another way to look at Sandberg’s all-around ability. His career high in steals was 54 in 1985. He led the National League with 40 home runs in 1990. The only other players with a 50-steal season and 40-homer season are Barry Bonds and Brady Anderson. There certainly are players today with a similar all-around game — we’ll talk about Ronald Acuna Jr. in a bit. Christian Yelich hit 44 home runs and stole 30 bases last year. Trevor Story has power, speed and great defense. Francisco Lindor, Mookie Betts and Cody Bellinger are power hitters and Gold Glovers, they and can run. In a different era, they might have stolen more bases or hit more triples. They are all appealing players, the best versions of today’s game. Sandberg was that player in the 1980s.

Tom Herr, 1985 Cardinals (8 HR, 110 RBIs)

Twenty-two players drove in 100 runs in 2019. Twenty-one of them hit at least 30 home runs, with DJ LeMahieu‘s 26 the fewest. The most RBIs for a player in 2019 who hit fewer than 10 home runs? Nick Markakis and Adalberto Mondesi, each of whom drove in 62 runs while hitting nine home runs. Nobody else drove in even 50. More than ever, runs now come via the home run. A season like Tommy Herr’s 1985 could not exist in today’s power-driven game.

How did he do it? Herr batted third in 151 games that season in a lineup with Vince Coleman as the leadoff hitter (149 starts) and MVP winner Willie McGee as the primary No. 2 hitter (120 games). Both of those guys could fly, and while Coleman had a mediocre .320 on-base percentage, he did steal 110 bases so he was often in scoring position. McGee hit .353/.384/.503 with 56 steals, so he was often in scoring position as well. They combined for just 11 home runs, so they weren’t driving themselves in, leaving more RBI opportunities for Herr. He hit .302 overall and thrived with runners on base — .356 with runners on and .333 with runners in scoring position. Herr’s job wasn’t to hit home runs; it was to hit singles and doubles and drive in the runner on base.

The Cardinals of the ’80s under Whitey Herzog played a unique style of offensive baseball, but it worked. In 1985, they ranked 11th of 12 teams in the National League with just 87 home runs, but still led the league in runs scored as they led in batting average (.267), OBP (.335) and stolen bases (314). Five players swiped at least 30 bases, including Herr with 31.

Herr’s type of season used to be a regular occurrence 80 and 90 years ago, when the tops of lineups featured players with high batting averages, usually in front of a big slugger or two. Since 1920, there have been 69 seasons of 100-plus RBIs and fewer than 10 home runs, but 59 of those came in the ’20s and ’30s. Since 1950, however, there have been just three: George Kell in 1950 (8 HRs, 101 RBIs), Herr, and Paul Molitor in 1996 (9 HRs, 113 RBIs).

Could a team like the 1985 Cardinals exist and win today? The 2014-15 Royals sort of fit that mold. They ranked last in the AL with 95 home runs in 2014 and first in steals with 153, but that also wasn’t a great offensive team, at least until the postseason, ranking ninth in the league in runs. The 2015 Royals hit 139 home runs and stole 104 bases — not really all that similar to the 1985 Cardinals — and ranked just sixth in the AL in runs. Home runs and strikeouts have only increased since then, making even the idea of building a team around speed and singles hitters instead of home runs an even dicier proposition.

The other question here gets to the heart of nostalgia: Do you prefer Picasso or Degas? Do you prefer home run or stolen bases? Maybe the answer is “both.”

Mark Eichhorn, 1986 Blue Jays (14-6, 10 saves, 157 IP, 1.72 ERA)

This season is so uniquely wonderful on so many levels, starting with those innings pitched, all of which came in relief. Here is one way to look at Eichhorn’s rookie season. Working backward from 2019, here are the “records” for most relief innings in a season (not counting Ryan Yarbrough‘s “bulk” innings with the Rays in 2018):

Sam Gaviglio, 2019: 95⅔

Anthony Swarzak, 2013: 96

Scott Proctor, 2006: 102⅓

Scot Shields, 2004: 105⅓

Steve Sparks, 2003: 107

Scott Sullivan, 1999: 113⅔

Duane Ward, 1990: 127⅔

Mark Eichhorn, 1987: 127⅔

Mark Eichhorn, 1986: 157

A relief pitcher in the current era tops out at around 90 innings, with fewer getting over 80. Eichhorn threw 157! He threw at least three innings in 26 of his 69 appearances, including a high of six. Because he often entered with the score tied or the Jays down a run or two, he won 14 games. Via Baseball-Reference WAR, it’s one of the greatest relief seasons of all time:

Goose Gossage, 1975: 8.2

John Hiller, 1973: 7.9

Mark Eichhorn, 1986: 7.3

Bruce Sutter, 1977: 6.5

Ted Abernathy, 1967: 6.2

Eichhorn had briefly reached the majors in 1982 as a conventional overhand pitcher, but after suffering shoulder problems and a decline in velocity, he dropped down to submarine style in 1985, à la Dan Quisenberry. It was a last resort. “I just lost my stuff. One more year and I could have been out of baseball,” Eichhorn said in 1986. The new style helped his shoulder. He started exercising with three-pound weights at Triple-A in 1985 and felt strong enough later that season to raise his arm level to more of a sidearm delivery, similar to Joe Smith today, almost leaping sideways off the mound as he uncoiled.

Eichhorn had been a minor league free agent after 1985, but re-signed with the Jays. Nobody else was interested, and a cheeky note in Sports Illustrated said the Blue Jays invited him to major league spring training only because they needed somebody to throw batting practice. A key was developing a changeup that spring that made him effective against left-handers. One scribe said he threw the “slowest unhittable pitches in the league.” Batters hit just .192 against him, with right-handers a helpless .135.

In 2020, submariners still exist — Tyler Rogers of the Giants and Adam Cimber of the Indians serving as the most extreme examples. A few others like Smith and Steve Cishek throw from a low angle as well, so this type of pitcher hasn’t died off. But the idea of reliever throwing so many innings and being as valuable as the best starters in the league? That’s not happening.

Eric Davis, 1986-87 Reds (162 games, .308, 47 HR, 98 SB)

Maybe no other player from the ’80s inspires that sweet nectar of nostalgia like Davis. Part of it is a what-if scenario. What if Davis had been able remain healthy? Part of it is a “Did you see him play?” Just the other day, somebody on Twitter posted a video of Davis hitting a home run off Dave Stewart in the 1990 World Series, his hands dangling low in the strike zone and over the plate, the bat waving around like he’s about to pull a rabbit out of a magic hat. “Growing up watching the Reds, he was THE definition of cool,” responded one reader. “No one ever has the hand speed of Eric the Red,” said another.

“You’re in love with a fantasy,” Gil’s girlfriend, Inez, says to him at one point in the movie. Except with Davis, for one calendar year that fantasy was absolutely, unabashedly true. From June 11, 1986, to July 4, 1987, Davis played 162 games, starting 152 of them. He hit .308/.406/.622 with 47 home runs, 98 stolen bases, 149 runs and 123 RBIs.

In July of 1986, Davis hit .381/.465/.702 with six home runs and 25 stolen bases in 26 attempts in 24 games. “The statistics look imaginary,” Joe Posnanski wrote two years ago at MLB.com. “Think of Eric Davis as the greatest folk hero of them all.” Sports Illustrated put Davis on its cover in May of 1987 and compared him to Willie Mays, Hank Aaron and Roberto Clemente.

“Eric,” said Reds teammate Dave Parker in Ralph Wiley’s story, “is blessed with world-class speed, great leaping ability, the body to play until he’s 42, tremendous bat speed and power, and a throwing arm you wouldn’t believe. There’s an aura to everything he does.”

Davis tried to deflect the comparisons. “I’m being compared to the impossible,” Davis said. “What about the people I face every day? Tim Raines is the best? [Don] Mattingly is the best? Why not compare me to my peers?”

They couldn’t. For that brief moment when Davis was the best in the game, they couldn’t.

Jose Canseco, 1988 A’s (.307, 42 home runs, 40 stolen bases)

Maybe I shouldn’t include this one. After all, Ronald Acuna Jr. almost went 40/40 in 2019, finishing with 41 home runs and 37 steals. He could do it, if the ball stays juiced and he keeps running, although he’ll have to decide whether it’s worth it to put his body through the punishment of stealing bases. Mike Trout stole 49 bases as a rookie and then 33 as a sophomore and was down to 11 steals last season.

Before Canseco, Bobby Bonds had been the king of the 30/30 season, accomplishing it five times. Dale Murphy in 1983 became the first non-Bonds player to do it since 1970, and four players did it in the rabbit-ball season of 1987, including Davis, who finished with 37 home runs and 50 stolen bases. In spring training of ’88 Canseco made his goal loud and clear: He would become baseball’s first 40/40 player.

He boasted of his speed. “People see me run, and they say I look lazy, lackadaisical,” Canseco said that season. “Then they time me, and they can’t believe it. I’ve done a 3.8 from home to first, and that’s from the right side of the plate. I’ve run races against just about everyone in this organization, and no one’s beat me yet. My stride is deceptive.”

The chase was on after a quick start. The Miami Herald, his hometown paper, ran an ongoing 40/40 update on Canseco. He was the biggest story in baseball that year, at least until the Dodgers upset his A’s in the World Series. He led the league in home runs and RBIs and was the unanimous MVP winner. Canseco had made the power-speed combo a thing. The number of 30/30 seasons peaked in the 1990s, and Barry Bonds, Alex Rodriguez and Alfonso Soriano eventually joined Canseco in the 40/40 club, but the decline in stolen bases has led to a decline in 30/30 seasons:

1920s: 1

1950s: 2

1960s: 2

1970s: 5

1980s: 7

1990s: 20

2000s: 17

2010s: 10

Of course, Canseco’s season was the firestarter for another baseball topic that would heat up in the 1990s: steroids. Late that September, Washington Post columnist Thomas Boswell went on CBS’ “Nightwatch” with Charlie Rose and declared Canseco the “most conspicuous example of a player who has made himself great with steroids” (although Boswell never made the allegation in the paper itself). Boswell added that other American League players called steroids “a Jose Canseco milkshake.” Canseco denied the accusations.

Orel Hershiser, 1988 Dodgers (23-8, 2.26 ERA, 15 CG, 8 SHO)

There is the 59 consecutive scoreless innings, of course. That remains the record.

There is the 15 complete games, which has been equaled by just two pitchers since — Jack McDowell in 1991 and Curt Schilling in 1998 — and is 12 more than anybody threw in 2019.

There is the eight shutouts and … well, only five teams had even more than one shutout in 2019. (The Indians led with five.)

There is the 267 innings, which nobody came close to in 2019, although it’s worth noting that Hershiser threw 3,535 pitches in the regular season that year, fewer than Trevor Bauer (3,687) or Lance Lynn (3,553) threw in 2019.

All that is remarkable, a result of the era in combination with Hershiser’s greatness. It takes more pitches to rack up strikeouts, so pitchers now can throw just as many pitches or nearly as many over a season while throwing many fewer innings overall.

But here’s why Hershiser is included here: his postseason run. Check this:

Oct. 4, NLCS Game 1: 8⅓ IP (ND)

Oct. 8, NLCS Game 3: 7 IP (ND)

Oct. 9, NLCS Game 4: ⅓ IP (got the save)

Oct. 12, NLCS Game 7: 9 IP (shutout)

Oct. 16, World Series Game 2: 9 IP (shutout)

Oct. 20, World Series Game 5: 9 IP (win)

If you’re counting the days of rest, that’s 3, 0, 2 (or 3 since his last start), 3 and 3. That’s four starts on three days of rest, including two shutouts.

I know, you’re thinking of Madison Bumgarner from 2014, and that also was a historical run. Until his final relief appearance in Game 7, however, Bumgarner made all his starts on four days of rest. Put it this way: Hershiser pitched 42⅔ innings over 17 days; Bumgarner pitched 52⅔ innings over 29 days. In 2019, however, only two pitchers started even a single postseason game on three days of rest (not counting relief appearances): Justin Verlander and Dallas Keuchel.

At the end of “Midnight in Paris,” Gil realizes he needs to embrace the present instead of romanticizing the past. He breaks up with Inez and goes for a walk along the Seine late at night. It starts raining. He bumps into Gabrielle, a woman who runs an antique stall where Gil had bought an old record. They both love Paris in the rain.

The 1980s were wonderful, but I’m ready for some baseball.