ON APRIL 27, 1997, Chris Webber and the Washington Bullets were visiting the Chicago Bulls for Game 2 of their first-round playoff series. It didn’t go well.

Michael Jordan went off, scoring 55 points, equaling his highest output since he returned from retirement in 1995. It was an amazing display, but how he did it was telling. MJ didn’t nibble around the edges or hunt foul calls all night. He made just one 3-pointer. He had 10 points at the line. He scored 42 on 2-point field goals alone.

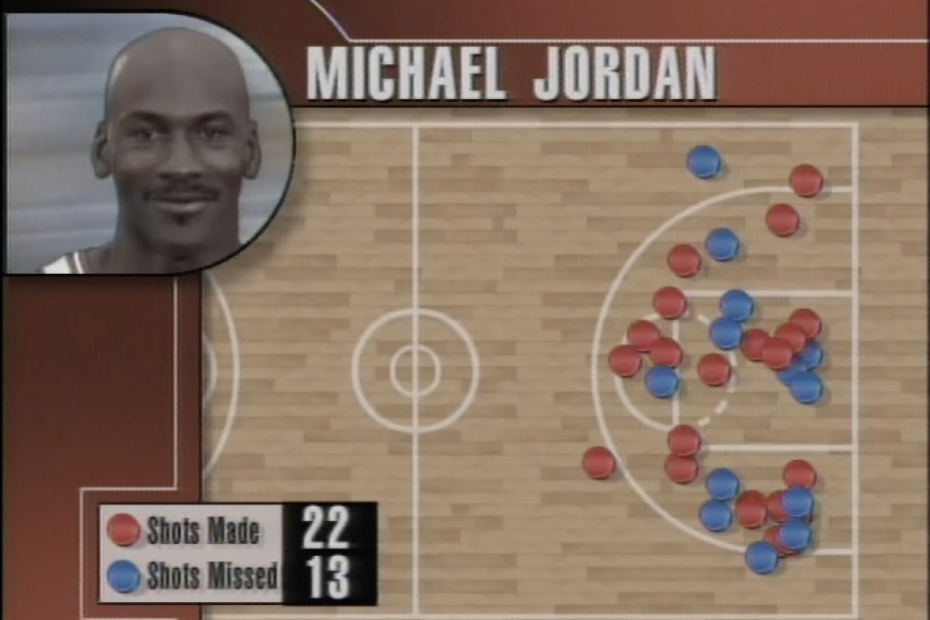

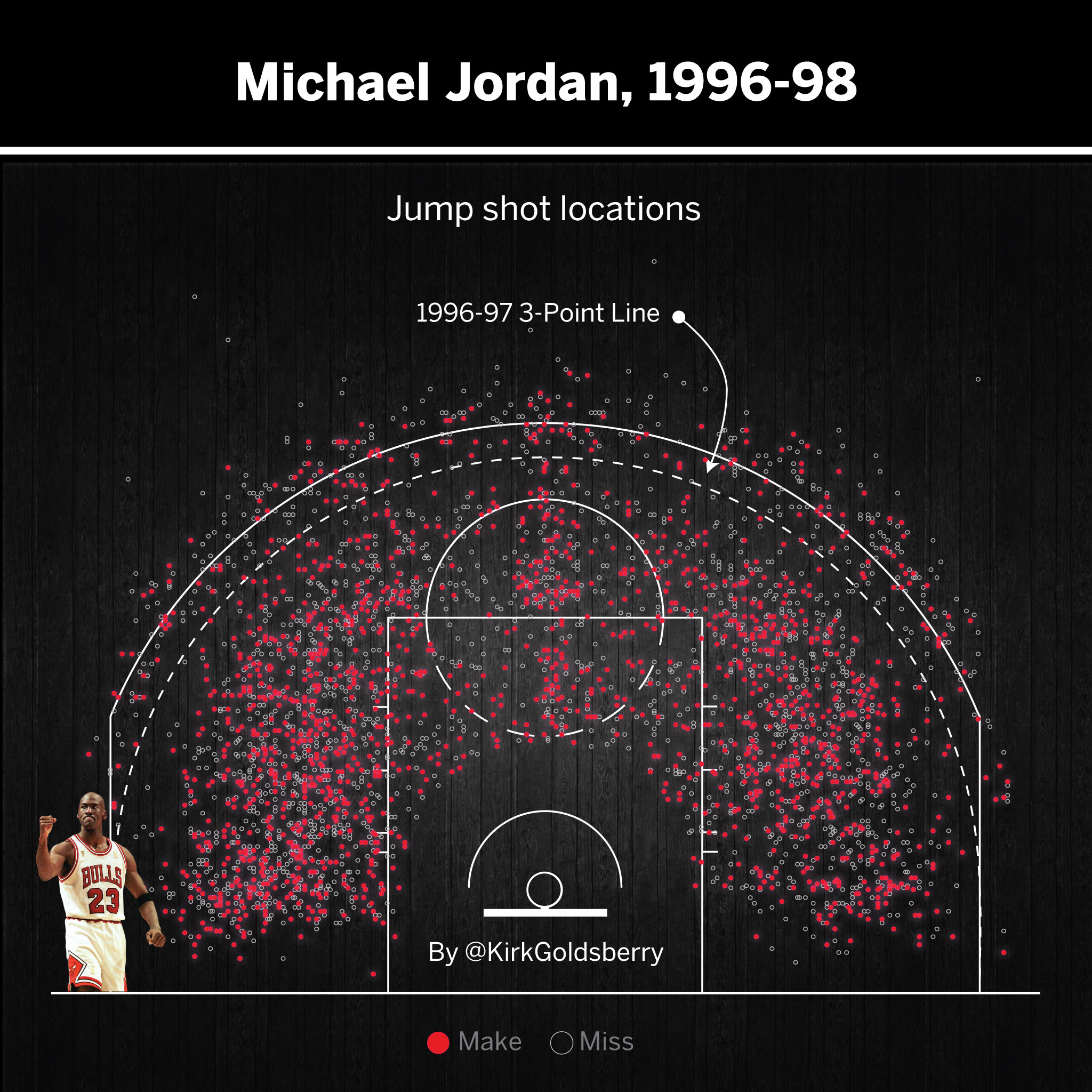

Check out all those red dots in the midrange in this vintage NBC shot chart:

Jordan scored 20 of the Bulls’ 23 points in the fourth quarter of a close game. His usage rate was an absurd 45%, but he was efficient, needing just 35 shots to get his 55 points. The rest of the Bulls scored 54 points on 43 shots.

That season, Jordan won his ninth scoring title and his fifth NBA championship. He was on top of the basketball world. But something else happened: The NBA began recording estimated X-Y shot location data. That’s how we know that while Jordan led the league in scoring in 1996-97, he ended up tied for 57th in the NBA in points in the paint and 54th in made 3s per game. Just like he did versus the Bullets in Game 2, he dominated from the midrange.

That shot location data set the stage for a new way to evaluate players’ abilities. This piece — which, via the NBA, uses access to the shot locations for nearly every attempt dating back to the 1996-97 season (five of MJ’s games and 1.4% of all shots leaguewide weren’t tracked that season) — is possible thanks to that initiative.

Today, we have technology that allows us to track the most intricate on-court details in any game. That wasn’t the case when Jordan played. But after accessing the NBA’s historical shot location data and accounting for the brief use of a 22-foot 3-point line before it moved back to 23.75 feet in 1997-98, we can understand MJ’s scoring prowess in fascinating detail.

More than 20 years since Jordan retired, it’s clear that the ways he created all those buckets were not just gorgeous and effective — they were singular. Jordan thrived in ways and in places that few players before him could match, and that even fewer players today can emulate.

Jordan entered a league that belonged to size and strength. By the time he walked away, he showed us once and for all that great jump-shooters can win both scoring titles and NBA championships.

MORE: How to watch ESPN’s Michael Jordan documentary this Sunday

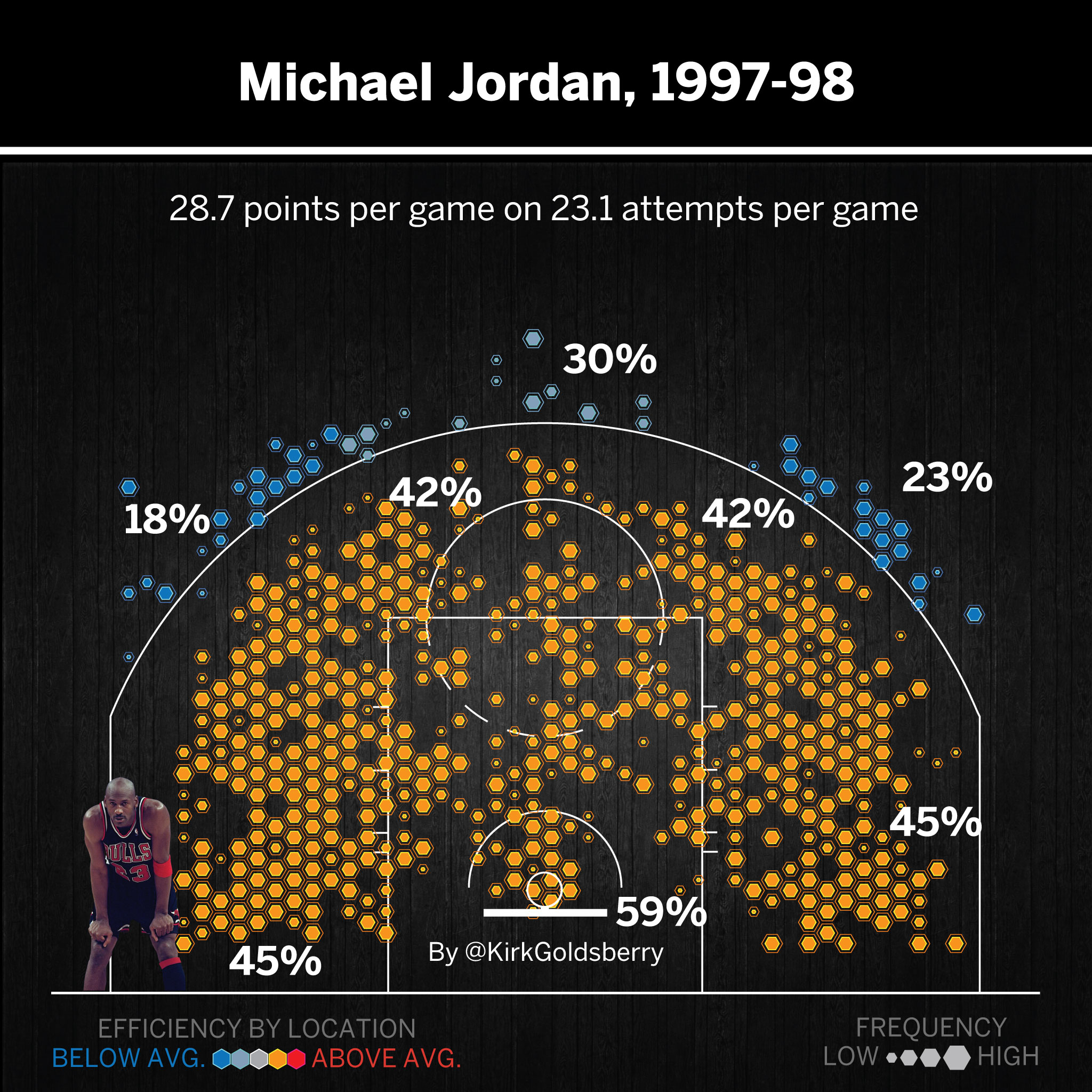

STUDYING JORDAN’S OLD shooting data reveals a couple of fascinating things. First: MJ was not only the greatest scorer of his era, but he was a hyperefficient shooter, too. We didn’t use the word “efficiency” much when talking about hoops in the 1990s, but Jordan passes the efficiency test with flying colors.

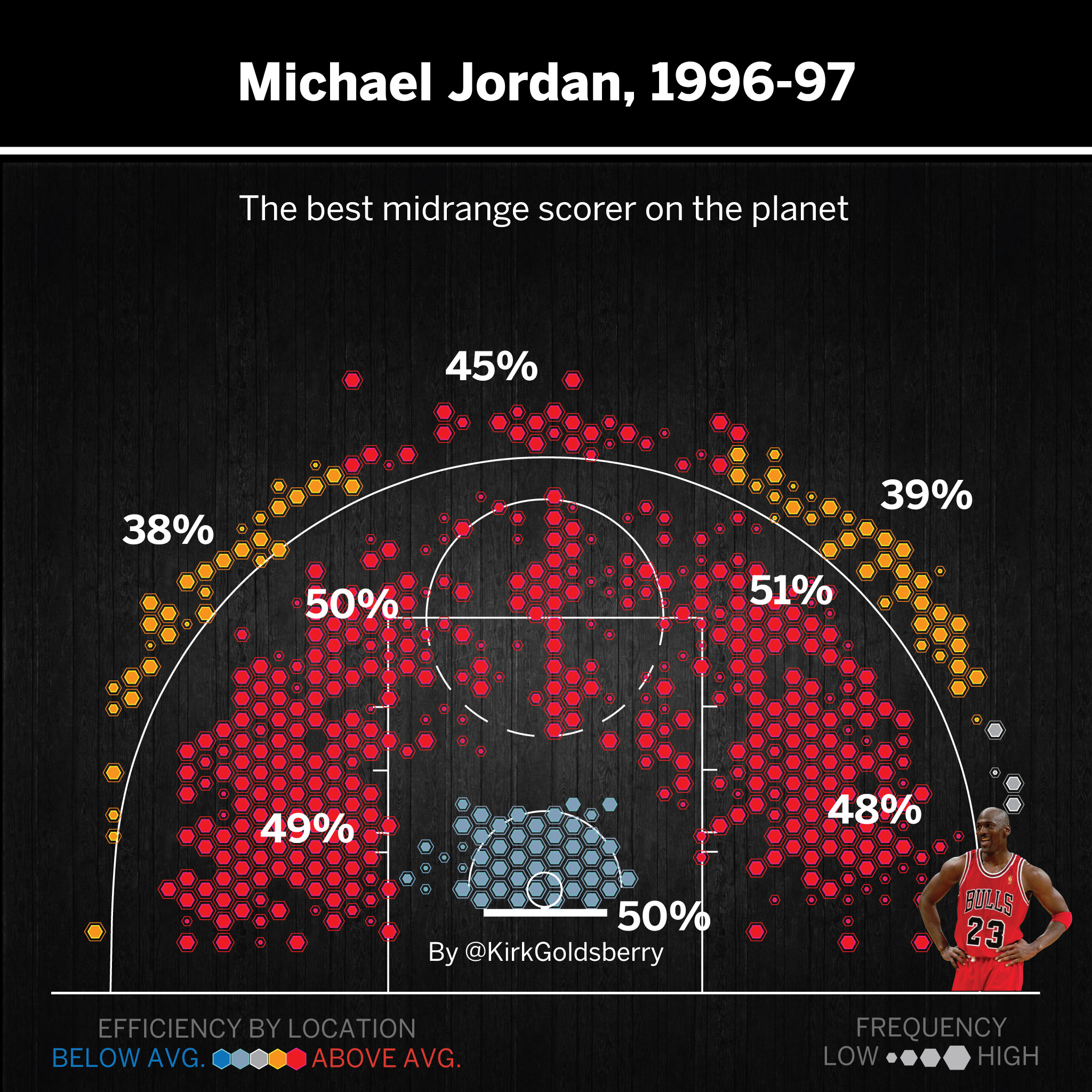

Just look at this. That’s a lot of red, folks:

During the Bulls’ second three-peat, Jordan won three consecutive scoring titles. His go-to shots in that legendary period were no longer the incredible gravity-defying dunks that marked the early stages of his career, but rather some absolutely gorgeous midrange jumpers (defined here as any attempt between 8 feet from the rim and the 3-point line).

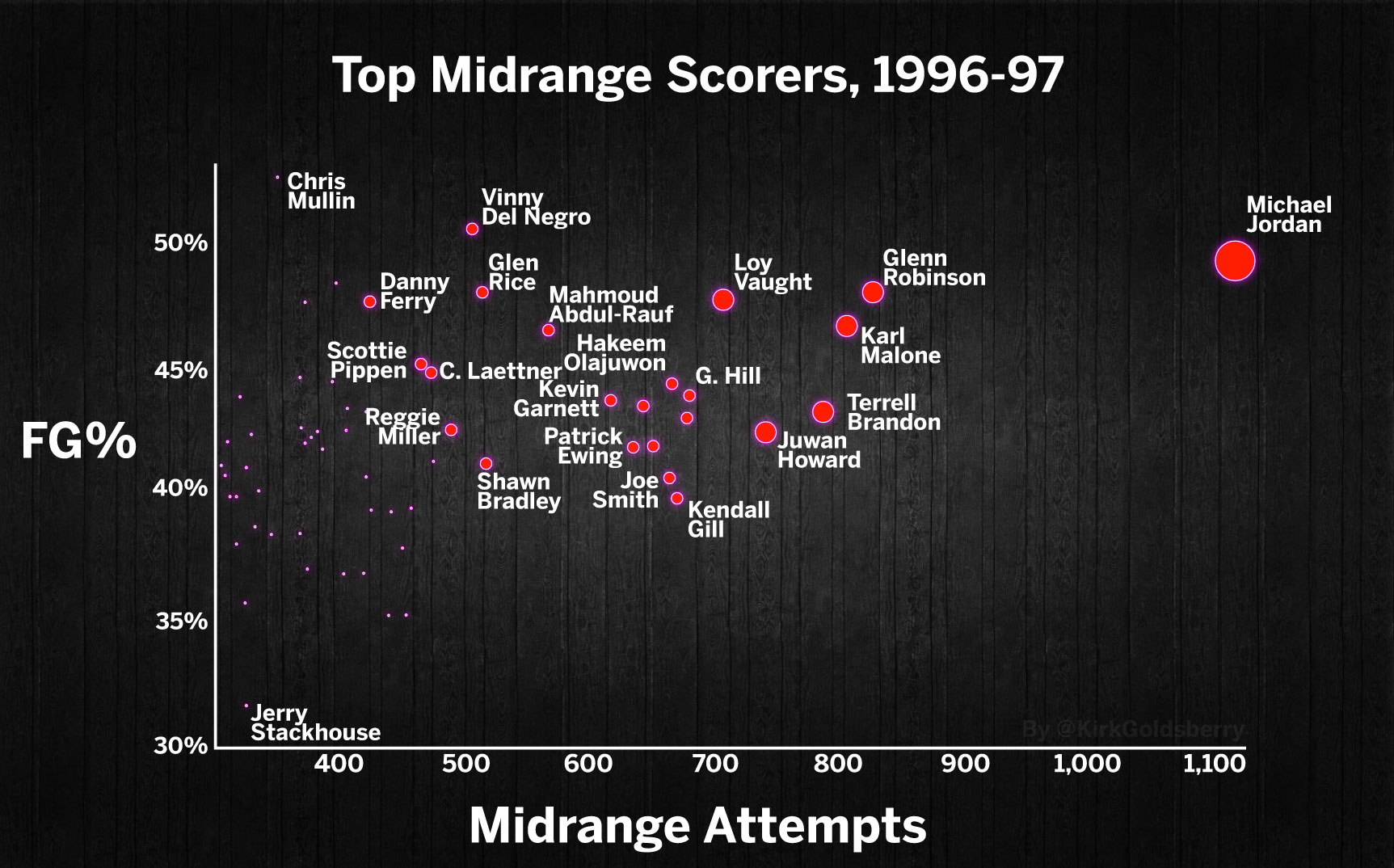

Jordan wasn’t just the most active 2-point jump-shooter in the world, he was arguably the most efficient one, too. Consider these two nuggets:

-

In 1996-97, Glenn “Big Dog” Robinson ranked second in midrange scoring, pouring in 391 field goals from that zone. Jordan made 547.

-

Of the 59 NBA players who attempted at least 300 midrange shots that season, Jordan ranked third in overall efficiency, hitting 49.5% on over 1,100 tries. Only Chris Mullin and Vinny Del Negro were more accurate. Reggie Miller, commonly regarded as the finest shooter of that era, made 42.4% of his 484 midrange shots that season. Yep, Miller attempted 484 while Jordan made 547.

Jordan ranked first in midrange scoring and third in efficiency despite his midrange game requiring him to take numerous impossible shots against the league’s top defenders on a nightly basis. With all due respect to Mullin and Del Negro, they were not the centerpiece of every opponent’s game plan. They were not the focus of all the eyeballs in every arena.

In the NBA in 1997, there was Michael Jordan, and then there was everyone else:

Still, to fully absorb how special Jordan’s late-era Bulls numbers were, you not only have to understand that he put them up in the face of astounding amounts of defensive pressure. You must also recognize that at one point in his career, his jumper was the weakest part of his game.

“When we looked at him for the draft, he was 195 pounds and 6-6, so he was kind of thin,” said Rod Thorn, the Bulls’ GM when Chicago drafted Jordan. “So the biggest thing about him was, can he make a shot?”

It didn’t happen overnight, but Jordan eventually became the most fearless, most clutch and most terrifying jump-shooter of his era. He mapped out the future of the sport.

Years later, Phil Jackson, the coach who witnessed Jordan leverage his maniacal work ethic to transform from a rim-attacking leaper into one of history’s most important jump-shooters, said: “The weakest part of Michael’s game on the offensive end was his shooting, so he obviously mastered something that everybody said he couldn’t do when he came out of college. And he did it by shooting, shooting, shooting, shooting consistently.”

Not only did Jordan slowly build up one of the most reliable jumpers in the NBA, he also engineered brilliant ways to get to this signature move.

THE CHANGES IN NBA superstar scoring over the past 20 years have been drastic.

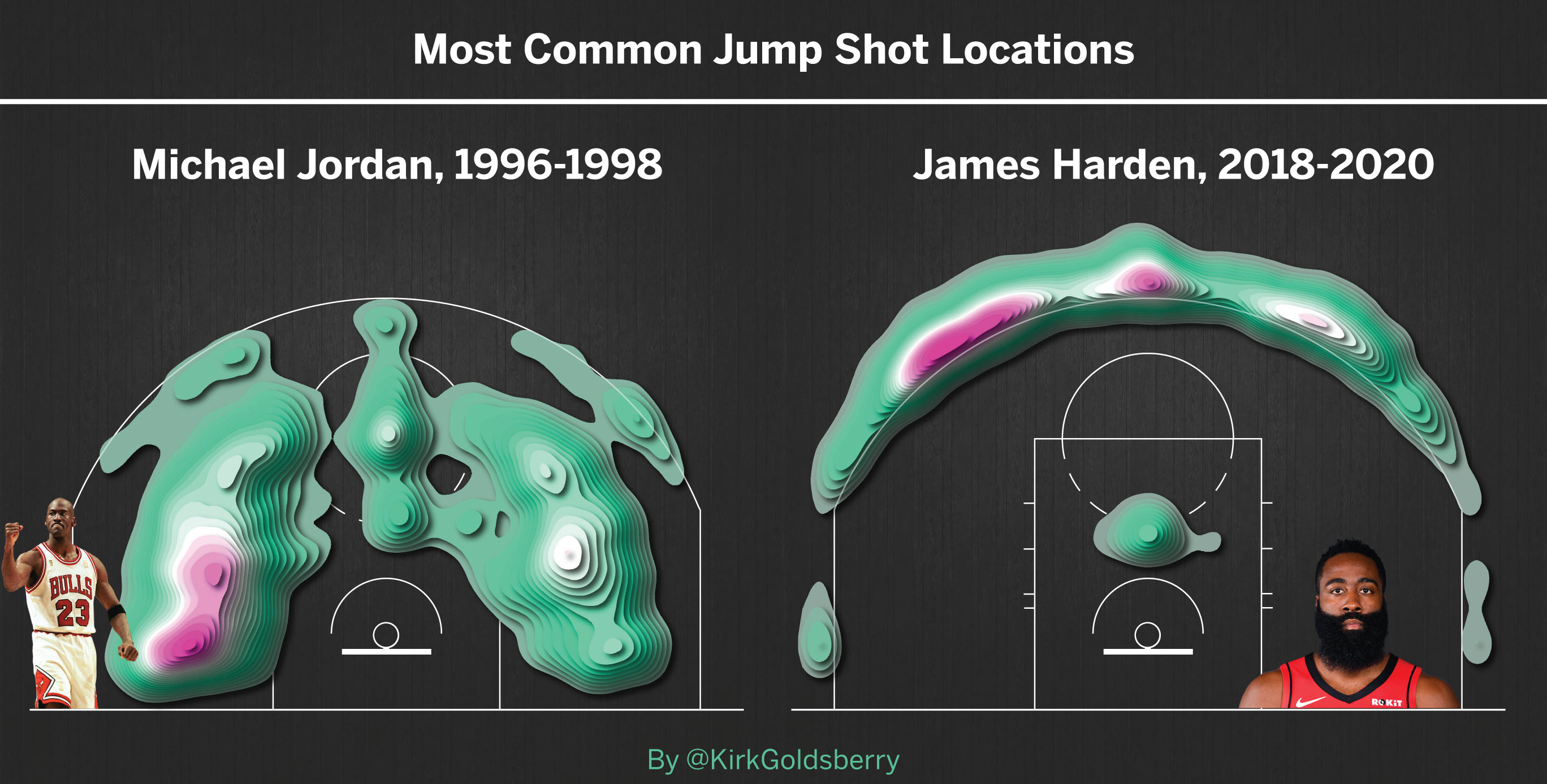

Here are Jordan’s favorite jump shot locations from his last two Bulls seasons alongside James Harden‘s past two campaigns. Both Jordan and Harden have won multiple scoring titles from the shooting guard position, but the similarities end there.

Jordan didn’t dance around the margins of the scoring era. He infiltrated the teeth of opposing defenses and destroyed them up close and personal. He said it to their faces. Other players will win scoring titles and NBA championships, but nobody will ever do it like Jordan did.

In fact, since the NBA moved the 3-point line back in 1997, no one has come close to topping Jordan’s mark of midrange makes in a season.

Most midrange buckets in a season (since 1997-98)

-

1997-98 Michael Jordan: 671

-

2005-06 Dirk Nowitzki: 564

-

2003-04 Kevin Garnett: 540

-

2000-01 Glenn Robinson: 506

-

2005-06 Kobe Bryant: 502

-

2008-09 Dirk Nowitzki: 501

In the spring of 1997, Steve Smith, one of the most gifted wing defenders of his era, described defending Jordan in detail to Sports Illustrated. The challenge was as much mental as it was physical.

“Somebody like Reggie Miller will run you back and forth across the floor through a million picks on every possession,” Smith said. “But Michael doesn’t waste much motion, he doesn’t play with you … When he gets the ball, he lets you get set, then he does what he’s going to do.”

The 1990s Bulls weren’t hunting mismatches every trip down the floor. Jordan was the mismatch. There was a cruel intimacy to his domination. Defenders had no excuses.

It’s not that MJ was averse to attacking a compromised defender — it’s that he was so freakishly comfortable beating the league’s best defenders from scratch, over and over again. Jordan would catch the ball, pause a moment, the crowd would anticipate, then he’d just go get a bucket.

Defending MJ meant facing an endless and unpredictable array of one-on-one moves and simply hoping shots wouldn’t fall.

“He had no pattern,” Smith said. “He went left, he went right. He drove, he pulled up. When he gets like that, you just have to do your best and hope he eventually cools off.”

Jordan was so fun to watch because these one-on-one sequences made for incredible entertainment. As soon as he caught the pass, the whole crowd knew the best player in the world was about to pounce — they just didn’t know how.

If he had a signature shot in the second three-peat, it was his stunning fadeaway. Jordan didn’t invent the fadeaway — post players had used it for years before him — but nobody moved like Mike, and Jordan turned fadeaways into artwork.

The beauty and effectiveness of those jumpers turned the exact kinds of ho-hum, back-to-the-basket, post-up chances that defined basketball for generations into breathtaking, must-watch television. Those jumpers also allowed the Bulls to run a simple offense, something that came in handy within the brutality of 1990s hoops: Just get MJ the ball in the post.

By the second three-peat, Jordan had become maybe the best post-up guard in history. If you look at Jordan’s jump shot locations between 1996 and 1998, you see tons of activity near the left and the right block areas:

This is where Jordan would break out the “windshield wiper,” his nickname for his favorite fadeaway variation where he faked a turnaround over one shoulder and then sprang back and shot over the other.

Generally, post defenders overplay one side, and Jordan designed his fadeaway to exploit that. This iconic move fueled countless buckets in the late stages of Jordan’s career, and became a playground trick for a generation of young hoopers doing their best to “be like Mike.”

The windshield wiper also highlights the thoughtfulness behind MJ’s approach.

As his incredible athleticism began to wane in his 30s, Jordan knew he had to keep his defenders off balance. When he sensed his defender was leaning too far one way, he could flip the script, glide into a clear shooting pocket and let his old-man jumper do the rest.

Before Jordan, fadeaways were frowned upon by many coaches. You weren’t supposed to shoot the ball while moving away from your target. While MJ acknowledged that in training videos, he countered that with proper practice, the shot could become a reliable weapon.

Like all transcendent superstars, he created new fundamentals, and in the post-Jordan NBA landscape, the fadeaway jumper became a cornerstone of many of the league’s greatest shooters. It’s not a coincidence that players such as Kobe Bryant and Dirk Nowitzki rode fadeaways and midrange jumpers all the way to the top of the NBA in the years following Jordan’s retirement.

AS BEAUTIFUL AS Jordan’s approach was, it was also exhausting. MJ’s magnificence was running on fumes as he won his 10th scoring title in 1997-98. His fatigue manifested in reduced efficiency in his favorite spots.

He was still the best player in the world that season, but he was no longer the best version of himself.

Still, Jordan managed to pull his team through the postseason gauntlet one last time in the spring of 1998, thanks in large part to his midrange prowess. In that postseason, 56% of Jordan’s buckets came in the midrange zone. The 34-year-old ended the postseason with 136 made midrange shots and just 13 made 3s, but of course it was his final shot from that last dance that we all remember.

When Jordan sank that iconic dagger to sink the Jazz in the 1998 Finals, Bob Costas said it perfectly:

“If that’s the last image of Michael Jordan, how magnificent is it?”

It’s not just that he was the most aesthetically magnificent superstar that basketball has ever seen. It’s not just that Jordan was statistically incredible. It’s not that he became a brand unto himself before that was even a thing. Of course he did. But he also showed us that guards who can shoot can dominate the best basketball league in the world.

Coming into the 1984 draft, 16 of the NBA’s previous 20 MVPs were centers. No shooting guard had ever won even one MVP award. Jordan transfigured the look and feel of basketball greatness, reshaping and elevating it beyond anyone’s expectations.

Jordan showed us that jumpers could quell giants and conquer the sport at the highest level. To “be like Mike” isn’t just to win 10 scoring titles, six rings, five MVPs or to sell millions of signature shoes. You also must permanently reform the nature of your sport.

When Jordan left the NBA, the league belonged to skill and speed. It still does.