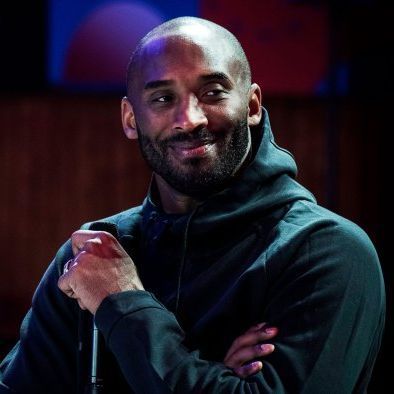

When Kobe Bryant wanted to talk, he’d shoot you a text or email: “When are you headed this way again?” This was his way of suggesting the booking of a flight. A one-man news cycle, almost anything Bryant shared became a story. He never seemed to grow tired of the swirl surrounding him. In fact, it fueled him.

In most of these interviews, Bryant endeavored to send a message to management or coaches, teammates or opponents — sometimes all of those constituencies in a single sitting.

Back in November of 2010 — and unknown to me — the target was Michael Jordan. The Los Angeles Lakers had won back-to-back championships and Kobe had moved within a title of catching MJ’s six rings. Jordan had said something that felt like a slight to Bryant — leaving him off some sort of list of great players.

When asked about Jordan, Bryant had an opening to tell me his story about Michael Jackson. He told of the pop icon calling him when he was with the Lakers, telling Bryant he could sense that he was taking a lot of grief for being different and that they should get together and talk. This was something Bryant had never discussed before, and I remember my eyes darting back and forth to my tape recorder, fearing a malfunction.

Inside the fourth floor of a Minneapolis hotel restaurant, Bryant was unloading about the late King of Pop and himself. I’ll always remember his jacket — purple and gold, with five Larry O’Brien trophies emblazoned across the back and sleeves. He looked like the varsity letterman wearing his state title patches at the Friday night pizza haunt. Kobe Bryant was 32 years old, and he didn’t care at all.

“We would always talk about how he prepared to make his music, how he prepared for concerts,” Bryant told me. “He would teach me what he did: how to make a ‘Thriller’ album, a ‘Bad’ album, all the details that went into it. It was all the validation that I needed — to know that I had to focus on my craft and never waver. Because what he did — and how he did it — was psychotic. He helped me get to a level where I was able to win three titles playing with Shaq because of my preparation, my study. And it’s only all grown.

“That’s the mentality that I have — it’s not an athletic one. It’s not from Jordan. It’s not from other athletes.

“It’s from Michael Jackson.”

The thing is, Michael Jordan was everything to Kobe Bryant. He wanted MJ’s blessing, the way a generation of players wanted Kobe’s. Jordan was never close to Bryant, and Bryant was never close to LeBron James, and that’s just how it goes with most of these iconic stars. The competition is cutthroat — and it doesn’t matter whether they’re competing in real time or for the historical narrative. In the age of player empowerment, Bryant took great pride in something few others might have considered as part of their lifetime achievement: He never had to take a pay cut to win a championship.

Once, we were having dinner at Javier’s in Newport Beach and out of nowhere began one of our strangest conversations: Kobe was convinced that Lakers president Jim Buss wanted to amnesty the remaining money and years on his contract and force him to leave the Lakers. He had no evidence, just a hunch.

“That is never happening,” I told him. “They’d burn the city down.”

“I think he wants to do it,” Kobe insisted.

Well, what would happen then?

“I’ll go to New York and play for Phil [Jackson].”

There was no reason to believe Buss ever considered it, but Kobe couldn’t stop talking about it that night. In some ways, it was a rare crisis of confidence for Bryant. He had to understand that the Lakers would never cut him loose. Still, he kept coming back to the idea over that long dinner.

We connected a couple of weeks later, and he no longer seemed concerned about the Lakers amnestying his contract. Kobe was on to something else, because he was always on to something else.

I was driving on Sunday afternoon, talking with a front-office executive about the upcoming trade deadline, when suddenly I told him I’d have to call him back. My phone began bouncing with a barrage of texts. I pulled over and tried to understand what had happened.

Word of a helicopter ride on a Sunday morning to what sounded like a basketball game with his daughter Gianna. Lakers president and GM Rob Pelinka — Bryant’s former agent and, perhaps, his closest friend — had recently been regaling me with stories about Kobe’s passion for coaching Gigi’s teams. Once I had the information verified and reported, there was still a part of me expecting Kobe to reach out and tell me, “Hey man, you bleeped up! I’m here!”

Now the loss of nine lives in the crash, the impact to families and friends and loved ones, is beyond measure.

One of the best parts of this job had long been that random text or email, wondering: “When are you coming out again?” For the longest time, Kobe Bryant had been the center of so many of our lives. That’s the hard part today, because he had so clearly become the center of his little girls’ world; and all that’s gone now.

I always suspected Gigi and her three sisters had gone a long way to give their father’s life clearer purpose. Did they change him? I don’t know. I do believe they made him a better man, the way most children do for their dads.

The rest of us will survive without hearing from Bryant again, but his wife and those young girls, well, that’s an emptiness and loss that no story and no 81-point night and no championship could ever touch. After 20 seasons with the Lakers and legitimate global domination, these had been Kobe Bryant’s best years, his finest performance.

Father and daughter courtside in Brooklyn, talking ball, smiling, edging close — that’s an image for the ages too now.