It has been a popular parlor game among league executives all season: How good will the Golden State Warriors be if Kevin Durant leaves?

You can’t draw a direct line from the 73-win Warriors — the last pre-Durant version — to the theoretical 2019-20 team. Harrison Barnes is gone. Andre Iguodala, dunking and stripping the ball and prancing all over these playoffs, is 35. Shaun Livingston is in the final stages of a wonderful career. Their low first-round picks haven’t yielded much in the way of starter-level contributors — the cost of greatness. The three original stars are on the wrong side of 30, or approaching it.

The tenor of that parlor game changed during the first round this postseason. The eighth-seeded Clippers swiped two games at Oracle Arena, and pushed the Durant-era Warriors to a distance only one other team had managed. Stephen Curry looked mortal. Durant went berserk and rescued them. The same pattern repeated over the first three games of the Rockets series.

It seemed like the Warriors needed Durant to go berserk. That did not portend well for next season. Maybe we shouldn’t pencil them in as no-brainer favorites in the Western Conference. Maybe it’s time to lump them in with Houston, Utah, Oklahoma City, Denver, Portland and whomever wins the free-agency derby.

Maybe not. Golden State is now 31-1 in its past 32 games when Curry plays and Durant does not — and 34-4 in such games since signing Durant. The sample size is growing. It suggests the Warriors remain a different style juggernaut when their founding stars are healthy and motivated, and know they have to make do without the star who joined.

It can be hard to see that juggernaut — to close your eyes and see it — when Durant plays. That was almost the point of signing him. He could blend with Steve Kerr’s share-the-wealth ethos, but also enable a more traditional style.

It hasn’t always been easy to mesh the two in the half court. Against some teams — particularly those, like the Rockets, who switch — the Warriors default more to slower mismatch-hunting centered around Durant’s one-on-one scoring. Golden State’s other three stars can still fly around when Durant has the ball.

But by their own admission, they sometimes downshifted. They stood and watched. Cut at half speed. Slipped screens without the usual jarring ferocity.

It wasn’t always easy for Curry, Klay Thompson and Draymond Green to flip the turbo switch. They didn’t have to with Durant around. When he rested, the three were rarely on the floor together. The regular season is overlong and boring for a team headed to its fifth straight NBA Finals. Green was out of shape until a planned March diet.

Like anyone subsisting on pull-ups, Durant suffers the occasional cold night. Those nights — when Durant missed more and the other three stars didn’t or couldn’t summon their pre-Durant verve — are when you saw the illusion of a less than dominant post-Durant future.

These past six wins, and the synergistic dominance of Golden State’s founding fathers, have been a reminder: We are still here. They may not win the No. 1 seed in the West without Durant; they have earned the right to coast and rest. But they will be in the championship picture when it matters.

Let’s take a deeper look at how the Warriors tapped back into their roots, with some help (some sources on-the-record, some anonymous) from coaches and players who faced them recently.

The dread split

Curry and Thompson comprise the greatest shooting backcourt in history, and maybe (definitely?) the greatest backcourt ever, period. Kerr’s most important big-picture change upon replacing Mark Jackson was leveraging the power of the Splash Brothers’ shooting when they didn’t have the ball. The split action — two players coming together and bursting apart — existed long before the Warriors, but Curry and Thompson weaponized it to a degree never seen.

In the play above, CJ McCollum and Evan Turner switch, and all appears fine. But as Curry collides chest-to-chest with McCollum, and stands McCollum almost upright, he senses a chance to back cut.

Green bounces a pinpoint pass. Maurice Harkless steps up off Kevon Looney to snuff Curry’s drive. Curry bounces to Looney, who lays the ball in as Harkless flails at shadows.

What are you supposed to do here? Perhaps McCollum and Turner should stay home instead of switching; McCollum almost dips down into Curry’s pick, surrendering to a switch before he needs to. As the Rockets showed last season, part of a sound switching scheme against Golden State is feeling out when not to switch.

In theory, Damian Lillard might bolt down from Alfonzo McKinnie and smother Looney. Lillard is the fifth defender Golden State yanks into the action in about two seconds. Almost no defender can snap from “out of the play” to “urgent rotation” so quickly.

It has been good sport to poke fun at the “Kumbaya Kerr” egalitarian offense, but the results have proved Kerr right. Unleashing Curry and Thompson as cutters has paid dividends beyond keeping role players involved and happy enough to try hard on defense.

It maximizes Green, one of the great playmaking big men ever. It unlocks easy looks around the basket for role players who would be useless in standstill spot-up roles. Top-heavy superteams scrounge for minimum-salaried support. Such players come with holes in their games. Many are bad shooters. The magnetism of Curry and Thompson as cutters opens crevices through which the Looneys and Iguodalas and Livingstons and McKinnies and Zaza Pachulias and JaVale McGees and Jordan Bells can slice.

The uh-oh 3

Most opposing defenses have reasonably adopted a strategy of ignoring anyone who is not Curry, Thompson or Durant to help on Golden State’s historic trio of shooters. But with Curry and Thompson always moving, you never know where those shooters might pop up.

The uncertainty clouds the brains of those roving help defenders — even with Durant out.

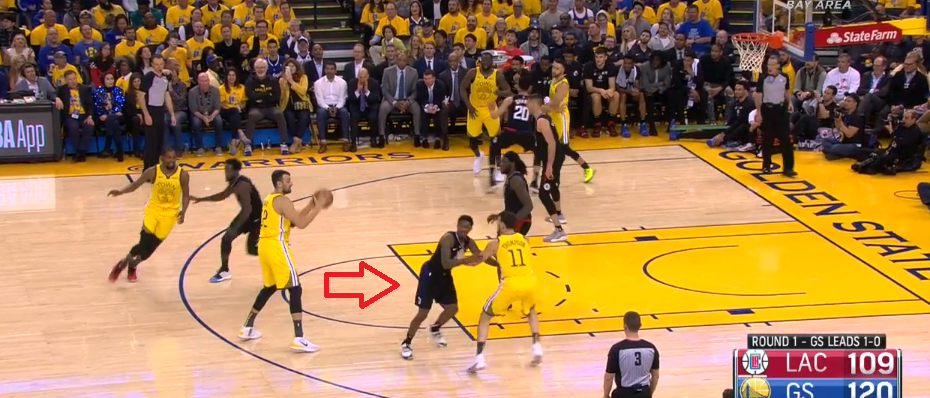

This is a classic Golden State action, though they prefer to do it with Durant posting up and Green in Looney’s role here as screener.

“It is their single best play and the hardest one to guard,” says Doc Rivers, whose Clippers took the “ignore role players” strategy to an extreme in the first round.

Enes Kanter is nominally on Looney, but he’s 15 feet away from Looney so he can help on whatever more dangerous threat might appear.

But Kanter is not really helping on anyone. He’s chilling near Green, even though there is no need to swarm Green on the block. Kanter doesn’t bother swiping at Looney’s entry pass. As Krusty the Clown once barked at another overmatched opponent, “JUST TAKE IT! TAKE THE BALL!”

From there, it’s over. Curry rockets around Looney’s pick, knowing Kanter has no chance to cover all that ground.

“You have to recognize the guy you are not guarding on purpose is now setting a screen, and run back up, and that is really hard,” Rivers says. “You cannot get paralyzed.”

It takes a rare combination of alertness, anticipation and speed to toggle in an instant from “ignore” to “pressure” — as Harkless managed on Green here:

Harkless is a wing. Big men — like Zach Collins below — are more prone to paint-bound paralysis:

In convincing opponents they need to help so dramatically off every non-shooter — that a threat could appear anywhere, that you need to be all places at once — the Warriors mind-trick them into helping on ghosts.

“They cause a lot of confusion,” Meyers Leonard says days after the Warriors swept Portland. “It’s incredibly difficult to be a help defender and then be up at the screen. It feels awkward. Help defense against the Warriors is totally different when they are playing that old Warriors style. It’s not normal. You never know what’s coming.”

Rivers was watching that game and laughing in exasperation at that Curry 3-pointer, he says. Notice how both of Looney’s screens direct Curry toward the coffin corner. Most pindowns spring shooters away from the boundaries. The Clippers blocked Curry and Thompson from using those picks — “top-locking,” in hoops parlance:

The Warriors countered by redirecting their offense toward the corner. “They are so smart,” Rivers says. He took particular note of the way Curry shoved his backpedaling brother into Looney’s pick. Mean.

Golden State is preposterously good within tight confines. Their offense blooms in environments — the corners — where for most it withers.

Thompson understands the power of his shooting — that a double-team might come. Livingston knows what pass he’s going to make before he gets the ball. Should the Blazers have switched? Probably. Try making that read in real time. Should someone have rotated down to Bell? I guess. The passes just come too fast. Golden State has prized pass-and-cut IQ in role players because the way they play — the broader identity that is an extension of Curry — requires it.

The inherent challenge of Golden State (with or without Durant) is that there is no one catch-all answer to defending them, or even to defending any one of their players over any single possession. Sometimes, you should switch. Sometimes, you should roam. Sometimes, you should trap. Sometimes, you should do all of those things in rapid succession.

A lot of those strategies are in direct conflict. Say you are a shot-blocker defending Green on one wing while Curry dribbles on the other. You should get ready to help at the rim on Curry’s drive, right? But wait! Green is setting an off-ball screen for Thompson. Your job is to switch such actions. How can you switch outside onto Thompson and help inside on Curry?

You can’t. If you’re switching you can’t help, and if you’re helping you can’t switch, and trying to figure out which to do depending on a dozen variables — who has the ball, how much time is left on the shot clock, what other Warriors are on the floor, whether Joe Lacob is taunting you — can plunge the smartest defenders into a haze.

“It’s like you’re in a boat with three holes in the bottom,” Jeff Bzdelik, Houston’s former defensive coordinator, told me last season, “and you only have two pegs to plug them. You just have to keep moving the pegs around.”

Rivers resorted to telling his players to hack when they felt themselves falling behind. “That was the first time I had ever done that as a coach,” he says.

Adding another mean layer

This is the same setup, only the Warriors add a fourth player — the other Splash Brother — to the strong side. They transition from the split cut into the Green screen so seamlessly it is all just one liquid action.

Thompson cuts before screening for Curry, and slices behind McCollum. That forces Leonard to sag away from Green, and from there you are in Prayer Mode.

“You’re thinking, ‘OK, I’m helping on this cut from Klay, but there’s Steph up there, and, oh no, I’m going to be late,'” says Leonard, who was at the center of this play. “You’re always worried.”

One potential counter: Harkless could peel off Green, account for Thompson, and hope one of McCollum or Leonard reads that — and jets out toward Looney/Curry. That kind of improv is a lot to ask given all of Golden State’s moving parts. Scripting it ahead of time risks paralysis-by-overpreparation.

A variant of the same split-into-screen combination:

Leonard’s help is required here too — first on Curry cutting across, then on Thompson zipping backdoor. Even so, it takes Leonard out of position for the crescendo Curry-Green handoff.

This is why Rivers says he adjusted the Clippers’ help rules after Game 1 of that series: ignore non-shooters unless they have the ball, in which case, please, for the love of the basketball gods, get up on them.

Going that route puts pressure on the guys guarding Thompson and Curry to navigate the Splash Brothers Ballet without exposing any holes. The two Portland defenders in question fail here.

There is a basic principle beneath all this whirring motion: The Warriors want to force the same defender to scurry into the paint to find one Splash Brother, and then back out to find the other. It can be as simple as linking a Curry pick-and-roll with a handoff for Thompson:

That is a lot of back-and-forth travel for poor Kanter.

Where it all started

And in the end, there is this, over and over until you submit to the hyper-speed dominance of perhaps the greatest pick-and-roll combination since John Stockton and Karl Malone:

Curry ran fewer pick-and-rolls this season than at any time since his ascension to stardom, per Second Spectrum data. Six of his 20 highest volume pick-and-roll games of the season have come since Durant’s calf injury.

Green, as usual, is Curry’s dance partner of choice — an equal partner. Green kills defenses with the lob to Looney there. Livingston slips in to provide a second outlet. Lillard again fails to rotate, and again you can’t blame him; the Warriors involve four players — Curry, Green, Looney, Livingston — in the on-ball action in about two seconds.

Staying out of rotations is less taxing. That is why switching is in theory the optimal strategy against the Curry-Green two-man game. But few bigs can track Curry beyond the arc. He is an underrated isolation scorer in his own right — including against guards. Plopping a switchable wing on Green creates a trickle-down mismatch elsewhere.

When Durant plays, that mismatch is fatal. Without Durant, the Blazers felt comfortable playing three small guards together. Durant is Golden State’s bailout option — the trump card — against switch-everything schemes. He is insurance against icy shooting nights.

We’ll never really know if the Warriors needed Durant to beat the 2017 Cavs — LeBron’s best Cleveland team — or last season’s Rockets. It felt like they did, but it also felt like they needed him to outlast the Clippers three weeks ago. Maybe they needed him to become invincible — to be something more than a normal championship-level team. (It’s possible to be a championship-level team and not win the championship.)

It appeared at times this season as if they needed Durant to be merely that: a normal great team. The past two weeks have been an emphatic reminder: Maybe they don’t.